|

The Ephemeral Director

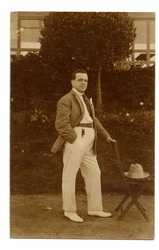

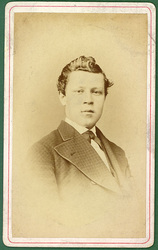

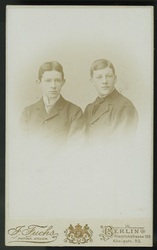

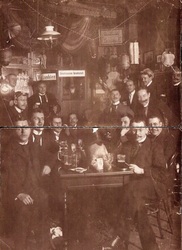

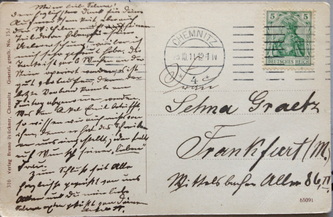

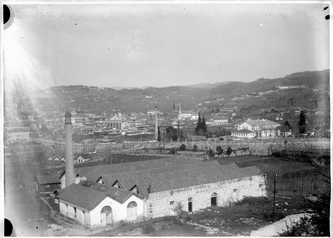

Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick [Chemnitz, Saxony, 4.1.1873 - Barcelona, Spain, 12.7.1936] A study by Eduardo Brito 1. Introduction Few Cinema lovers will have heard of Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick. However, if we were to cast an eye over any history of the textile industry in Portugal and Spain, the name would not be unfamiliar to those in the know. For, as an engineer at the start of the 20th Century, Meyersick was responsible for the assembly of countless weaving machines in a vast number of factories on the Iberian Peninsula, from Corunha to Huelva via Portugal. As a filmmaker, Meyersick, directed just two films: Der Schlingel / The Scoundrel (1920), in Portugal and El Impostor de Alcalá / The Imposter of Alcalá (1922), in Spain. But who was this shadowy character that Cinema has forgotten? Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick was born in Chemnitz in the heart of Saxony in 1873. He was the youngest son of Johann Heinrich Ludwig August Meyersick, director of the city’s Conservatory of Music, and Ninna Klara Hinkel, sister of the wealthy industrialist Freidrich Otto Hinkel. Conrad’s life was always linked to the language of invention. From a tender age, he displayed a particular appetite for machinery: as an infant and throughout his childhood he made himself familiar with designs for flying machines, enormous pin-hole cameras and even seven string violins, bringing together the legacy of his ancestors in all of these utopias. In 1896, after two years studying in Dresden, Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick travelled to Manchester to further his engineering studies at Victoria University. During his years as a student, Meyersick displayed a profound fascination with Cinema: lengthy were the descriptions of the sessions he attended at the St. James Theatre on Oxford Street, in the letters he wrote to his brother Kasper. In 1905 he went to Paris to get to know Louis Feuillade. Then, in 1910 he journeyed to Vienna, where the big names in German Cinema of the time were present. Meyersick remained in England for 10 years. After completing his studies he worked at Howard & Bullough in Accrington. The sudden death of his older brother in a sailing accident, forced him to return to Germany, in order to work at his uncle Freidrich Otto Hinkel’s factory, Moritz Rockstroh & Hinkel GmbH. And it was around this time, in mid-1907, that he became acquainted with Selma Graetz, with whom he would marry two years later, becoming inseparable from her for the rest of his life. Selma, a music teacher and theatre actress, was a cultured woman, with an aristocratic background and links to the Windsch-Graetz family. Restless spirits, they travelled to London, where they stayed for two years, sufficient time for Meyersick to become an engineer at Edwin J. Brett & Co., where he was responsible for the running and assembly of their machinery in the Iberian market. It was because of this, that early in 1913 the couple moved to Barcelona – centre of the Spanish textile industry – taking up residence in Carrer de St. Pau. Right from the start, Conrad and Selma submerged themselves in the cultural life of the city, frequenting the film sessions at El Gran Cine Kursaal in the Rambla de Cataluna and the Tivoli Theatre in Calle Caspe. Meyersick’s work did not allow him to spend lengthy periods of time in the Catalan capital. As team leader of the engineers at EJB & Co for the Iberian Peninsula, he would travel all over, installing and assembling machinery in what was a flourishing textile industry. However, with the onset of the First World War, Conrad’s travels were reduced to a minimum. The almost enforced sojourn in Barcelona made him live at close quarters with the local intelligentsia, who charmed by his knowledge of Cinema, would often invite him to comment on and discuss all sorts of films in coffee houses and cinemas. Meyersick was a regular presence at the gatherings in the Café Maison Doree, much frequented by local film lovers at the time, amongst them the legendary Fructuos Gelabert. It was around this time that he made the acquaintance of Anatole Thiberville, the French cameraman who would work with him on The Imposter of Alcala. And also Rino Lupo, the Italian filmmaker, known in Spain as Cesarino and who in Portugal, made another lost film The Devil in Lisbon. Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick first came to Portugal in July 1918. As soon as the war ended, the Portuguese textile industry experienced an explosion of production. The trade grew and became modernized. Meyersick, by then the biggest specialist in Jacquard weaving machines on the peninsula, was called in to install three such looms in one single factory on the outskirts of Porto. The success and reliability of his machines, allied with the speed of his assemblies and the low travel costs, would have opened up the Portuguese market to Edwin J. Brett & Co. And as a result, the German engineer, henceforward became a regular visitor to the north of Portugal. On one of these trips to the region located between the Douro and Minho rivers, Conrad made the acquaintance of James Lickfold, an English engineer, who had settled in the north and who two years beforehand had founded the Guimarães Steam Linen Factory – which later would merge with the Spinning and Fabric Company of Guimarães. Lickfold would have been responsible for selecting Meyersick and his team to install and assemble a line of Jacquards at the Avenue Factory in Guimarães, between February and July 1920. It was not long before the restless engineer who loved Cinema, would start shooting his first film, The Scoundrel. 2 – The Accidental Filmmaker Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick only made two films. The Scoundrel, dating from 1920, was partly shot in Guimarães, while the German was staying in the city. The Imposter of Alcalá, made in 1922, was filmed in the city of the same name and also Barcelona. The Scoundrel turns a fact into a story: on the 18th July 1839, the local paper recorded the death of Friar Domingos Pedreira, in Caldas das Taipas: “the scoundrel was killed by a blacksmith, with a rifle shot, after having committed the most heinous of crimes.” Using this as his starting point, the engineer-filmmaker, created the tale of a righteous avenger endowed with uncommon strength who, as a result of his unrequited love for an engaged woman, becomes a villain terrorizing a quiet town. The Imposter of Alcala, meanwhile turns a true event, which occurred in Alcala de Henares at the beginning of the 17th Century, when an actor who was missing his left arm, passed himself off as Miguel de Cervantes, into a cloak and dagger story. The films The Scoundrel and The Imposter of Alcala were never studied in any great depth and no documentation has been found to prove or disprove the few theories that have been put forward about them. The credits of both films prove only the obvious: Meyersick was responsible for writing and directing both and based them on local stories; Paul Oberstein, the engineer’s technical assistant, appears as the main character in the two films; and the members of the film crew are also workmates of the engineer-director. The rest of the characters, when they are not identified by name, are referred to as “a group of local actors”. 3. The German in town Let us return then to Guimarães: it is February 1920 and Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick arrives in town after an exhausting three-day journey from Madrid. Awaiting his arrival at the train station is Augusto José Domingues D’Araújo, majority shareholder and director of the Avenida Factory, who installed him in the Hotel Toural, a little less that five hundred metres from the factory where, every day for almost five months, Meyersick would install a line of Jacquards. It’s most likely that the German engineer became acquainted with the businessman and northern Cinema promoter, Luiz do Soto, not long after his arrival - the latter, being a regular presence at the hotel where they both stayed. If we might refer to his Memoirs of a Businessman (1938), and his venture to turn the Quinta Bullring into an open air cinema in 1920, we note the reference to a “German friend,” who “unfailing in these open air projections in the gardens of the Cine Gloria in Barcelona and the Paseo de Prado in Madrid”, would have been “the prime mover of the same idea in Salamanca in the Plaza Mayor,” two years beforehand. Who could this friend have been, if not Meyersick? Meyersick’s love for film did not go unnoticed in Guimarães. The city chronicles refer to him as the “robust German”, who never missed a cinema session at the Central Chantecler in the Rua de Gil Vicente, or at the High Life in the Campo de Feira. However, beyond these few details, everything is mere supposition: Meyersick could have come across the legendary story of the Scoundrel Friar Domingos through contact with the ethnography notes written by Martins Sarmento, which were probably made available by the Society of the same name. Liver of the high life, fluent in Castilian and a driving force in his field, Conrad Meyersick would easily have become known to the Grupo Scenico Choir, which was the most popular theatre group in the city at the time. And that is how one could explain the participation of two of its members in the cast of his film (Henriqueta Dionisio and Santo Rodrigues). An analysis of the screenplay and the fragments of film, which have survived until now, enables us to conclude that The Scoundrel was shot in May 1920 between Guimarães and Misarela Bridge in the Gerês Mountains. To go any further than that would be a speculative exercise: it’s likely that all the interiors were filmed at the Vila Pouca Palace, but this could also have taken place in another manor house in the city. Combining facts and speculation is how we could establish a possible theory about The Scoundrel: a work which reveals a thorough assimilation of the aesthetics and techniques of the Cinema of the time; a script that conveys the director’s fascination with bizarre and outlandish folklore, always sharpened with a fine slice of humour; a film that was shot in Guimarães simply because of the professional fate of its director. What is certain is that on the 22nd of July 1920, Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick checked out of the Hotel Toural, bid farewell to Augusto José Domingues D’Araújo and to the Avenida Factory and never returned to the city again, taking with him the film reels of The Scoundrel. Based in Barcelona, he would only return to Portugal once: in 1927 when he was in Lisbon at the invitation of his friend and director Rino Lupo. In 1922 Meyersick shot his second and final film: The Imposter of Alcalá. The exteriors were shot in the town of the same name, Alcala de Henares, whilst the interiors were filmed in the Pasage Mercaders, the headquarters of the producer’s society Regia Art in Barcelona. The film received little critical attention at the time of its release: The Imposter of Alcala was a film directed by a part-timer, who didn’t belong to any professional group. Meyersick was simply an aficionado who had neither the time nor the opportunity to break into the filmmaker circuits of the time. It was probably because of this and his repeated trips to Cantabria and Germany, that the German engineer stopped filming once and for all at this time. In July 1936, on the eve of the Spanish Civil War, Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick died peacefully in Barcelona, survived by his beloved Selma Graetz. 4. Films returns to being Cinema At the end of 2011, seven small fragments of this film reached the hands of Guimarães 2012, European Capital of Culture, via an anonymous Spanish collector, who revealed that he had bought them from a German at an auction that same year. A copy of the script and a handwritten note to a Cinema Professor in Berlin long since dead, were found along with these fragments. Henceforward, the story of The Scoundrel takes a better known route: by a quirk of fate as substantial as that which made Conrad Wilhelm Meyrsick shoot it in Guimarães, the film returned to its place of origin. The fragments of film and the script were the object of a meticulous study, the results of which were the remake of The Scoundrel in 2012 by Paulo Abreu, with a soundtrack provided by the musicians The Legendary Tigerman and Rita Redshoes. Whenever possible, Paulo Abreu’s film revisits the same locations as the original version: in terms of the general history of the small details, in the 2012 version the robbery scene in the museum and the meeting with the devil are filmed in precisely the same spots as its namesake of 1920: namely in the Martins Sarmento Society Museum and the Devil’s Bridge in Misarela. The same is also true of the title cards in German, which are faithful to the film fragments and screenplay: they were translated into Portuguese and remade with the same typographic fonts and graphics as the original. The memory of Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick, the ephemeral director thereby returns from the forgotten, along with the reinvention of his lost film The Scoundrel. Welcome back. Production Credits for The Scoundrel, in accordance with the film fragments and Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick’s script: The Scoundrel A Portuguese story in three Acts. Written and directed by Conrad Wilhelm Meyersick, 1920. Art Director: Richard Schwarze Director of Photography: Jorg Bauernhof Technician: Rudiger Bruchen Camera: Joszef Haube With: Paul Oberstein, Henriqueta Dionisio, Santo Rodrigues, Richard von Dreienigkeit, Estanislau dos Santos, Victor Blutner, Elizabete Galvão and a group of local actors. Production Credits for The Scoundrel, as re-filmed by Paulo Abreu (2012): Paulo Calatré – Scoundrel Tânia Dinis – Letícia Rodrigo Santos – The Devil Ricardo Vaz Trindade – Fiance’s friend Armando Morais - Thief Isabel Gaivão – Witch Sílvia Miranda – Letícia’s mother Armando Miranda – Letícia’s father Nuno Preto – Policeman Pedro Marinho – Gunman 1 Mário Gomes – Gunman 2 Eduardo Brito – Gunman 3 Director: Paulo Abreu Script: Eduardo Brito Director of Photography: Jorge Quintela Music: Rita Redshoes & The Legendary Tigerman Camera: José Capucha aka Torrão Producer: Rodrigo Areias Executive Producer: Ricardo Freitas Art Director: Ricardo Preto Special Effects: Júlio Alves Wardrobe: Susana Abreu and Sofia Torrinha Make up: Bárbara Brandão Equipment: Pedro Bastos and António Pedro Marinho Secretary: Luísa Alvão This work would not have been possible without the gratefully received help of Marcel Graetz, the great-great nephew of Meyersick, his only surviving relative and owner of the images of the director and his wife used herein. The author of this study would also like to recognize the worthy collaborations of José Manuel Cordeiro, Paulo Cunha and Victor Erice, as well as the Muralha Photography Collection. Translated by Sean Tuson. |